Rainbow trout

| Rainbow trout | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Oncorhynchus |

| Species: | O. mykiss |

| Binomial name | |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum, 1792 |

|

| Subspecies | |

|

See text |

|

The rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) is a species of salmonid native to tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in Asia and North America. The steelhead is a sea run rainbow trout usually returning after 2 to 3 years at sea. The fish is sometimes called a rainbow salmon. Several other fish in the salmonid family are called trout; the difference is often said to be that salmon are anadromous, whereas trout are resident.

The species has been introduced for food or sport to at least 45 countries, and every continent except Antarctica. In some locations, such as Southern Europe, Australia and South America, they have negatively impacted upland native fish species, either by eating them, outcompeting them, transmitting contagious diseases, or hybridization with closely-related species and subspecies that are native to western North America.[1][2]

Contents |

Taxonomy

The species was originally named by Johann Julius Walbaum in 1792 based on type specimens from Kamchatka. Richardson named a specimen of this species Salmo gairdneri in 1836, and in 1855, W. P. Gibbons found a population and named it Salmo iridia, later corrected to Salmo irideus, however these names faded once it was determined that Walbaum's type description was conspecific and therefore had precedence (see e.g. Behnke, 1966).[3] More recently, DNA studies showed rainbow trout are genetically closer to Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus species) than to brown trout (Salmo trutta) or Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar), so the genus was changed.

Unlike the species' former name's epithet iridia (Latin: rainbow), the specific epithet mykiss derives from the local Kamchatkan name 'mykizha'; all of Walbaum's species names were based on Kamchatkan local names.

The ocean going (anadromous) form (including those returning for spawning) are known as steelhead, (Canada and the United States) or ocean trout (Australia), although they are the same species.

Subspecies

A few populations are recognized as subspecies:

- Kamchatkan rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss mykiss (Walbaum, 1792).

- Columbia River redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdnerii (Richardson, 1836).

- Coastal rainbow trout/Steelhead trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus (Gibbons, 1855).

- Beardslee trout, isolated in Lake Crescent (Washington), Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus var. beardsleei (not a true subspecies, but a lake dwelling variety of Coastal rainbow trout) (Jordan, 1896).

- Great Basin redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii (Girard, 1859).

- Golden trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita (Jordan, 1892).

- Kamloops rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss kamloops (Jordan, 1892).

- Kern River rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus aguabonita gilberti (Jordan, 1894).

- Sacramento golden trout, Oncorhynchus aguabonita stonei (Jordan, 1894).

- Little Kern golden trout, Oncorhynchus aguabonita whitei (Evermann, 1906).

- Baja California rainbow trout, Nelson's trout, or San Pedro Martir trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss nelsoni (Evermann, 1908).

- Eagle Lake trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss aquilarum (Snyder, 1917).

- McCloud River redband, Oncorhynchus mykiss stonei

- Sheepheaven Creek redband, Oncorhynchus mykiss spp.

Life cycle

Like salmon, steelhead are anadromous: they return to their original hatching ground to spawn. Similar to Atlantic salmon, but unlike their Pacific Oncorhynchus salmonid kin, steelhead are iteroparous and may make several spawning trips between fresh and salt water. The steelhead smolts (immature or young fish) remain in the river for about a year before heading to sea, whereas salmon typically return to the seas as smolts. Different steelhead populations migrate upriver at different times of the year. "Summer-run steelhead" migrate between May and October, before their reproductive organs are fully mature. They mature in freshwater before spawning in the spring. Most Columbia River steelhead are "summer-run". "Winter-run steelhead" mature fully in the ocean before migrating, between November and April, and spawn shortly after returning. The maximum recorded life-span for a rainbow trout is 11 years.[4]

Feeding

Rainbow trout are predators with a varied diet, and will eat nearly anything they can grab. Their image as a selective eater is only a legend. Rainbows are not quite as piscivorous or aggressive as brown trout or lake trout (char). Young rainbows survive on insects, fish eggs, smaller fish (up to 1/3 of their length), along with crayfish and other crustaceans. As they grow, though, the proportion of fish increases in most all populations. Some lake dwelling lines may become planktonic feeders. While in flowing waters populated with salmon, trout eat varied fish eggs, including salmon, cutthroat trout, as well as the eggs of other rainbow trout, alevin, fry, smolt and even salmon carcasses.

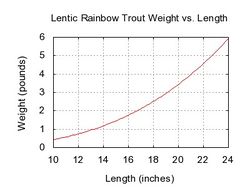

Length and Weight

As rainbow trout grow, they lengthen and increase in weight. The relationship between length and weight is not linear. The relationship between total length (L, in inches) and total weight (W, in pounds) for steelhead and nearly all other fish can be expressed by an equation of the form:

b is close to 3.0 for all species, and c is a constant that varies among species. For lentic rainbow trout, b = 2.990 and c = 0.000426, and for lotic rainbow trout, b = 3.024 and c = 0.000370.[5]

The relationship described in this section suggests that a 13 inches (33 cm) lentic rainbow trout weighs about 1 lb (0 kg), while an 18 inches (46 cm) lentic rainbow trout weighs about 2.5 lb (1 kg).

Threats and conservation

Steelhead trout population have declined due to human and natural causes. Two West Coast Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) are endangered under the Federal Endangered Species Act (Southern California and Upper Columbia River) and eight ESUs are threatened.[6] The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service has a detailed description of threats. Southern California (south of Point Conception) ESU steelhead have been affected by habitat loss due to dams, confinement of streams in concrete channels, water pollution, groundwater pumping, urban heat island effects, and other byproducts of urbanization.

The rainbow trout is susceptible to enteric redmouth disease. There has been considerable research conducted on redmouth disease, given its serious implications for rainbow trout farmers. The disease does not affect humans.[7]

The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service has identified 15 populations, called Distinct Population Segments(DPSs), in Washington, Oregon and California.[8][9] Eleven of these DPSs are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).[10] One DPS on the Oregon Coast is designated a U.S. Species of Concern. Species of Concern are those species that lack sufficient data to determine whether to list the species under the ESA.

Rainbow trout, and subspecies thereof, are currently EPA approved indicator species for acute fresh water toxicity testing.[11]

In 2010, the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife hatchery expects to more than double its take over 2009. The 2009 population grew 60% over 2008. Hatchery-taken fish will spawn tens of thousands of juvenile "smolts" that will be released to swim downstream and mature in the Pacific.[12]

In March 2010, the Los Angeles Times reported that the New Zealand mud snail had infested watersheds in the Santa Monica Mountains, complicating efforts to improve stream-water quality for the steelhead. According to the article, the snails have expanded "from the first confirmed sample in Medea Creek in Agoura Hills to nearly 30 other stream sites in four years." Researchers at the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission believe that the snails' expansion may have been expedited after the mollusks traveled from stream to stream on the gear of contractors and volunteers.[13]

Gallery

|

Male ocean phase steelhead |

Male spawning phase steelhead |

Steelhead attempting to jump some rapids |

Steelhead with clear spot pattern on fins and body |

Relation to humans

Fishing

Rainbow trout and steelhead are both highly desired food and sportfish. A number of angling methods are common. Rainbow trout are a popular target for fly fishers. Spinners, spoons, and small crankbaits can also be used productively, either casting or trolling. Rainbow trout can also be caught on live bait; nightcrawlers, trout worms, and minnows are popular and effective choices.

Hatcheries and farms

The first rainbow trout hatchery was established on San Leandro Creek, a tributary of San Francisco Bay. The hatchery was stocked with the locally native rainbow trout from local creeks. The fish raised in this hatchery were sent as far away as New York.[14]

They are farmed in many countries throughout the world. Since the 1950s commercial production has grown exponentially, particularly in Europe and recently in Chile. Worldwide, in 2007, 604,695 tonnes (595,145 LT; 666,562 ST) of farmed salmon trout were harvested with a value of 2.589 billion US dollars.[15] The largest producer is Chile. In Chile and Norway, ocean cage production of steelhead has expanded to supply export markets. Inland production of rainbow trout to supply domestic markets has increased in countries such as Italy, France, Germany, Denmark and Spain. Other significant producing countries include the USA, Iran, Germany and the United Kingdom.[15]

There are tribal commercial fisheries for steelhead in Puget Sound, the Washington Coast and in the Columbia River.

Cultivated varieties

Golden rainbow trout are bred from a single mutated color variant of Oncorhynchus mykiss.[16] Golden rainbow trout are predominantly yellowish, lacking the typical green field and black spots, but retaining the diffuse red stripe.[16][17] The palomino trout is a mix of golden and common rainbow trout, resulting in an intermediate color. The golden rainbow trout should not be confused with the naturally occurring golden trout.

As food

Rainbow trout is popular in Western cuisine and is caught wild and farmed. It has tender flesh and a mild, somewhat nutty flavor. However, farmed trout and those taken from certain lakes have a pronounced earthy flavor which many people find unappealing; many shoppers therefore ascertain the source of the fish before buying. Wild rainbow trout that eat scuds (freshwater shrimp), insects such as flies, and crayfish are the most appealing. Dark red/orange meat indicates that it is either an anadromous steelhead or a farmed Rainbow trout given a supplemental diet with a high astaxanthin content. The resulting pink flesh is marketed under monikers like Ruby Red or Carolina Red.

Steelhead meat is pink like that of salmon, and is more flavorful than the light-colored meat of rainbow trout.[18]

Medicine

The sperm of rainbow trout contains protamine, which counters the anticoagulant heparin. Protamine was originally isolated from fish sperm, but is now produced synthetically.

Native Americans used the skin of the rainbow trout as medicine.

See also

- Cutbow

- Fly fishing

- Golden trout

- Sport fishing

- Trout worms

Notes

- ↑ Salmo marmoratus

- ↑ Salmothymus obtusirostris salonitana

- ↑ Robert J. Behnke. 1966. Relationships of the Far Eastern Trout, Salmo mykiss walbaum Copeia, Vol. 1966, No. 2 (June 21, 1966), pp. 346–348

- ↑ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2006). "Oncorhynchus mykiss" in FishBase. February 2006 version.

- ↑ R. O. Anderson and R. M. Neumann, Length, Weight, and Associated Structural Indices, in Fisheries Techniques, second edition, B.E. Murphy and D.W. Willis, eds., American Fisheries Society, 1996.

- ↑ "Map showing endangered species status of west coast steelhead". Alameda Creek Alliance. http://www.alamedacreek.org/Steelhead%20trout/steelhead%20listing%20status.gif. Retrieved FEb. 14, 2010.

- ↑ LSC - Fish Disease Leaflet 82

- ↑ "Distinct Population Segments". U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/glossary.htm#dps.

- ↑ "Steelhead Distinct Population Segments". U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/ESA-Salmon-Listings/Salmon-Populations/Steelhead/.

- ↑ "Endangered Species Act". http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/laws/esa/.

- ↑ EPA Whole Effluent Toxicity

- ↑ "Fish Boom Makes Splash in Oregon". Wall Street Journal. January 21, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703657604575005562712284770.html. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Hard-to-kill snails infest Santa Monica Mountain watersheds Even Formula 409 has proven ineffective at destroying the New Zealand mudsnail, an asexually reproducing invasive species that poses a threat to steelhead restoration efforts and native creatures.

- ↑ About Trout: The Best of Robert J. Behnke from Trout Magazine By Robert J. Behnke, Ted Williams

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 FAO: Species Fact Sheets: Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792) Rome. Accessed 9 May 2009.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Golden Rainbow Trout. Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission FAQ.

- ↑ Golden Rainbow Trout. Photo.

- ↑ Your Christmas Steelhead

References

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2006). "Oncorhynchus mykiss" in FishBase. February 2006 version.

- "Oncorhynchus mykiss". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161989. Retrieved 30 January 2006.

- Scott and Crossman (1985) Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Bulletin 184. Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Page 189. ISBN 0-660-10239-0

External links

- Map showing endangered species status of West Coast steelhead

- Association of Northwest Steelheaders

- Fish-On! - Full Rainbow Trout Chapter at TheFishingNetwork.com

- Rainbow trout page from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game

- Rainbow trout information from Northern State University

- Australian Aquaculture Portal

- Fishbase.org article on Oncorhynchus mykiss, Rainbow trout

- Kenai River, Alaska Rainbow Trout Fact Page

- ZipcodeZoo fact page

- Season/Timing information for Steelhead in the Great Lakes region

- [1] Huge Alaska Rainbow Trout Photo Page

- Alaska Department of Fish and Game article on life cycle and conservation of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout

- Fishing the North Platte River

- GLANSIS Species FactSheet

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.png)